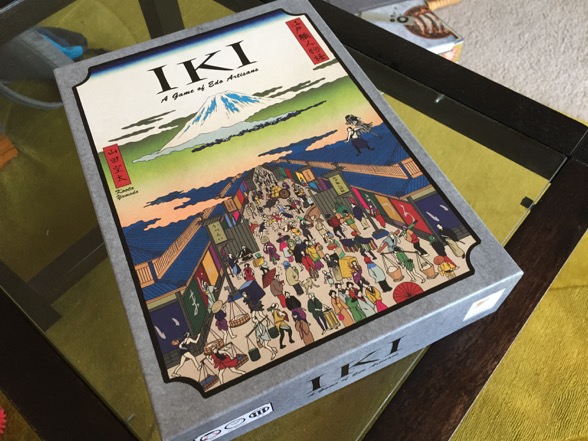

I may be an unabashed board game nerd these days, but it’s only because there are so many fun games out there. Truly — it’s a problem. An embarrassment of riches. Just when I think I can ebb the purchasing, another great one comes down the pike, the latest being Iki — a Japanese “game of Edo artisans.” Well, if that’s not a selling point, I don’t know what is.

I first learned about Iki during a particularly fruitful span of procrastination that had me exploring the depths of boardgamegeek.com. First, I came upon a glowing review of the game, and since it sounded interesting, I dug deeper until I found a playthrough on YouTube. After watching a few rounds of Iki, I went to the mirror and saw that I had giant hearts in my eyes. Oh dear. Time to make more room in my Ikea shelving system.

Iki is a nifty game that focuses on the Nihonbashi market in Edo period Japan (a.k.a. Tokyo). It’s kind of a very specific setting for a board game, and as per usual, I’ve already had several friends incredulously chuckle something along the lines of “Where do you find these games?” The truth is that there’s a game for seemingly every topic: pig farming in Mallorca (La Granja), winemaking in Tuscany (Viticulture), hotel management in Austria (Grand Austria Hotel), and on and on. At this point, a game about an ancient Japanese market almost seems rote.

Freaky Iki

Nevertheless, up to four players assume the roles of kobun — vague boss men whose responsibilities land somewhere between pimp and benefactor. You see, as an entrepreneurial kobun, you will undoubtedly hire a handful of people over the course of the game, all of whom will toil away to provide services to you and your opponents. These workers may vary from ear cleaners to geishas to glassblowers to samurais, and at the end of every season (each season spans three months/rounds), they will shower bonuses upon you. They may give you money or lumber or simply the titular Iki, which represents the spirit of the market (or, more technically, victory points). All these humble workers ask for in return is to be fed a few bales of rice. Is that asking too much?? Well, the answer to that is surprisingly tricky.

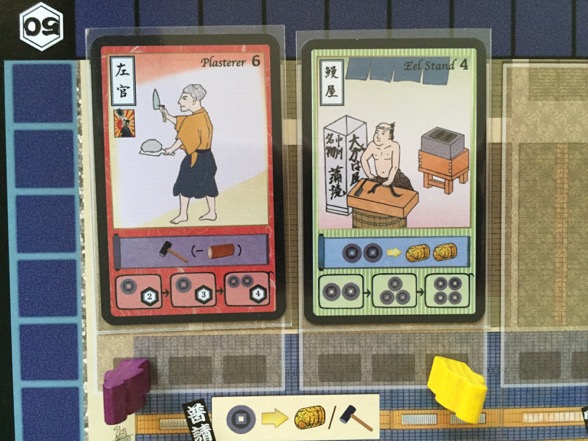

A small sampling of occupations. Note the different colors. The more colors you’ve collected by the end of the game, the more points you’ll score.

A smattering of resources: sandals, lumber, koban (the oval things), and rice bales.

Should you be unable to feed your workers, they will quit and leave the market for better opportunities elsewhere. However, if you can keep your peeps around long enough, they’ll actually gain “experience” over time and eventually retire. Once workers do that, they’ll still bestow gifts upon you, but you won’t have to feed their hungry asses. Such is the privilege of a DOTING KOBUN. And so it is in your best interest to help your underlings amass experience as quickly as possible in order to shove them into a post-employment state (which also contributes to end game scoring).

The salt peddler costs 0 coins to hire and gives a free rice bale to anyone who uses him. At the end of every season, he’ll give one coin unless he’s leveled up, in which case he’ll provide two coins instead (or a rice bale if he’s been leveled-up even more). By the time he retires, he’ll chalk up an ongoing bale of rice, which is an awfully convenient way to feed other workers.

So how does one get experience for workers? And where does one procure rice anyway? And how the HELL does anyone have enough money to hire any of these people in the first place??

The answers are in the market, my friend.

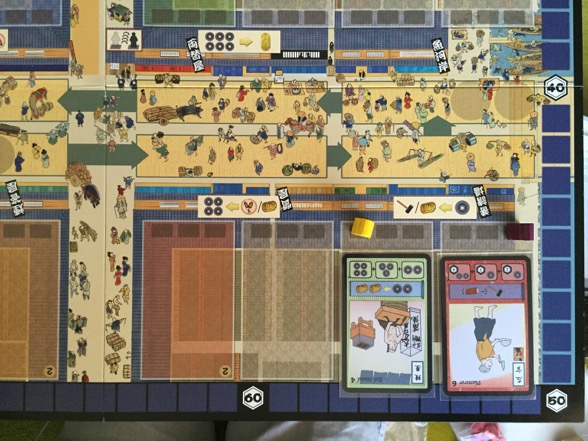

A scenic, birds-eye-view of the Nihonbashi market — or at least the board game version.

Little people stroll about the market, doing market-y things.

You see, after hiring a vendor (alternatively, one can just receive four coins), one advances through the market, which exists as an eternal, eight-space loop — or “rondel” — on the game board. One must circle through repeatedly until thirteen months have passed, at which point the game ends. During each tour of Nihonbashi, kobuns visit shops, amass wealth, acquire food, and occasionally do something perfectly lovely such as nab a fresh bonito fish in the summer months.

Springtime noodle fish wait to be purchased. Think of the bisque you could make! (People make noodle fish bisque, right?)

There are also opportunities to indulge in tobacco (as well as an accompanying pipe, should you feel so inclined to actually smoke that wacky tobacky) or perhaps grab a few pairs of sandals. Especially intrepid kobuns may collect lumber and a valuable currency known as koban, all in the pursuit of erecting a shrine, a merchant house, or — most excitingly — a kabuki theater!

The six buildings one can erect over the course of the game. These can be super powerful, but devote too much time and resources to them, and you’ll find yourself behind the curve or even worse: with a target on your back. Trust me: I speak from experience. (I just lost a game three hours ago thanks to a heavy building strategy).

The merchant house earns players three points for every sandal at the end of the game. Without this building, sandals are worth nothing. Such is the cruel fate of seasonal fashion.

I once used the merchant house to turn this stack of worthless sandals into a crushing powerhouse of points.

There it is: my blue guy standing guard over my merchant house. Meanwhile, a red meeple appears to be passed out in an empty market stall. Fear not: it’s just a reminder that in a two player game, the inner-corners of the market are off limits, as indicated by the limp meeple corpse.

Every point counts. The final score of this two-player game came down to a difference of two.

A busier board in a four-player game.

Tobacco pipes and pouches keep the game suitably smokey.

Each shop allows players to take an action (pay three coins to receive two bales of rice, for instance), and if someone has installed a worker or two at that location, there’s an opportunity to take an additional action, as dictated by the worker card. So, for instance, not only can you purchase those bales of rice, you can also receive a few coins from the cloth dyer, if he’s hanging around.

What’s even more fun is that if an opponent uses your employee’s action, that worker gains aforementioned experience — the very experience necessary to hasten retirement. Don’t worry though: if no one visits your lonely sushi stand, he will still level-up every time your kobun completes a lap at the market. In fact, all of your workers increase their experience a notch when this happens. Therefore it’s in your best interest to zip through the market as quickly as possible in order to advance your worker army towards retirement.

But is that the smartest thing to do? How are you going to feed your people if you’re running past the rice peddlers like a madman? And what if you need to pick up that bonito? Or a SEA BREAM?? (I should mention that those fish are worth mucho points at the end of the game). On second thought, you had better slow down, Mister.

But wait… if you just amble through the market with no urgency, your guys will take forevvvver to level up (because, let’s face it, none of your competitors are going to help your workers level up unless they truly have to). If you don’t sweep your guys into retirement, then you’ll have to feed them, and no one likes feeding employees (except, maybe Google). Oh, and there’s one other issue: players can only have four workers out in the market at any given time (less if they’ve constructed buildings). How frustrating to see waves of useful vendors go unhired because your stupid soap bubble man still hasn’t retired.

This is one of the central tensions and joys of Iki: does one move swiftly through Nihonbashi to retire workers? Or does one meticulously visit each shop along the way in order to make full use of the market’s powers?

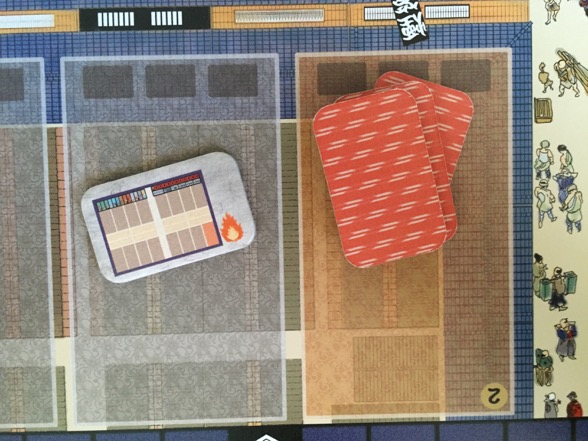

One of those extremely important powers is firefighting ability. Since this is a marketplace built of wood and paper, it’s not uncommon for a fire to occasionally sweep through and wreak havoc (something that apparently happened with great frequency in Edo period Japan). Fires in Iki will kill workers (RIP Eyeglass Peddler who I did not protect) and burn down structures. Therefore, players can — and should — spend some time improving their firefighting skillz.

Of course, one could simply ignore the firefighting track and gamble that the blaze will break out in a different corner of the market. Orrrr even better, a sneaky person could just place all their workers next to an opponent who has a high firefighting capability and essentially use them as a human shield. But that plan could backfire (no pun intended) should your protector suddenly retire and leave the market, exposing you to the brutal flames of fate.

A randomly drawn token indicates where one of the three fires of the game will flare up. In this case, the lower-righthand corner of the market.

Fires travel inwards from the outmost corner, getting weaker from stall to stall. In this case, the fire hits the plasterer (red card) first, and if the player who hired the plasterer has insufficient firefighting power, the plasterer DIES and the fire continues on to the eel stand.

This is that same corner, flipped upside-down. Now, let’s say the fire were a level 8 fire, and let’s say the yellow player had a firefighting power of 6. Well, that could be bad. The fire reduces in potency for every stall it moves through; so while the blaze would only be a 7 by the time it reached yellow’s eel stand, it still would be enough to burn it to the ground. But fear not! If the purple player’s firefighting power were 8, the fire would be put out, and the yellow player would be safe. And thus, placement of workers in relation to each other is SUPER essential, especially vis-a-vis fire strategies.

Having a strong firefighting power not only protects vendors and buildings, but it also offers a unique and important gameplay advantage. Whoever is farthest along on the firefighting track gets first dibs on the “Way of Life” track. This basically is how one determines how far in the market they’ll be moving — from one to four spaces. No two players can claim the same spot on this track, which means that if you need to go three spaces and someone else has claimed the 3 spot; you may be screwed (you can alternatively take the 1 spot and then use sandals to get extra movements in the market, but… if you don’t have sandals, you’re back to being screwed). And I can assure you of one thing: people will intentionally screw you out of movements if they see you’re headed towards a specific shop. In a four player game, having priority on the Way of Life track is essential. Whoever’s last must be content with whatever spot remains, or they can opt for a special action which allows them to travel any number of spaces — but they must forgo the opportunity to hire or collect money. Rough.

Because tokens atop a stack break ties, the yellow player is farthest along on the firefighting track and will therefore be first to choose how many spots to advance this round: one, two, three, or four.

Not all is lost, though. Whoever claims the least number of movements gets to resolve their turn first, which importantly means they’ll have first dibs on new workers (or that sea bream, which is in limited supply! Same goes for the tobacco and pipes — also worth many points). This all funnels back into that central tension of how quickly one rushes through the market. Those who fly through will most certainly get last pick of employees, but may get to perform vital actions more frequently. Those who take their time will get the best opportunities and hires — but may fall behind the firefighting / retirement pace.

GAH.

Even though yellow chose a spot on the Way of Life track first, the turns are resolved from left to right, which means that yellow will move last (and perhaps more importantly, hire last too).

Iki is all about trade-offs. No decision comes without a huge risk. Even placement of artisans can be fraught with multi-layered dilemmas. You might want to place a dice maker where it’s advantageous to you and your goals, but then no one may visit him. Alternatively, you might install him someplace where others are highly incentivized to visit him but is inconvenient to you. Also, outer market stalls are more vulnerable to fires, but inner stalls are more expensive. Oh, and did I mention that workers come in five different colors, and players receive seasonal bonuses if a bunch of like-colored workers are placed next to each other? That sounds great, but then at the end of the game, you’re rewarded for having a variety of colors. So, do you go for blocks of color throughout the game, or a set of all five colors for the end of the game? And what if someone places a folding fan maker RIGHT where you were going to put your croupier?? Now you have to weigh your options all over again from the start. UGH. (But it’s a fun “ugh”). This is just a fraction of the decision-making that Iki forces its players into.

It’s amazing if you think about it. All you’re really doing in this game is hiring, moving, and transacting, but the layers upon layers of strategy that develop are fascinating. Compounding this is the very high degree of player interaction. Y’all will be up in each other’s business. Perhaps you’ll be angling to hire the same dumpling peddler as your opponent. Or maybe you both want to land at a coveted shop to nab some firefighting boosts. Or maybe you’re both racing to the last tobacco pouch. Or maybe it’s an arms race to erect that fancy kabuki theater. Like a real market, there is jostling for position at all times.

A quick glimpse of the market before it fills up with workers, structures, and general chaos. Also note the essential wine accompaniment — always welcome at any market simulation.

In a four player game, things get crowded. We all have buildings up, which is cool, but players must assign one of their four worker meeples to structures for the duration of the game, which means there are fewer meeples available to hire vendors (each vendor needs a meeple to track its experience).

As the game progresses, strategies will coalesce, and soon your opponents will be able to anticipate your next move. Suddenly they’ll be snagging the Way of Life spot you so desperately need, forcing you to make one more hasty lap through Nihonbashi in order to land at the shop that would ordinarily be mere steps away.

Meanwhile, some of the occupations allow all sorts of nuanced, complicated player interactions. Take, for instance, a certain card that allows players to swap two vendors’ locations on the board. This can add such a layer of unpredictability to the game that it might be better to simply retire it off the board before it can do too much damage. But then you risk benefiting your opponent. THE CHOICES! SO MANY!

Yes, the gameplay in Iki is awesome, but making the experience all the more engaging and memorable is the game’s theme. Sure, Edo period Japan may not be everyone’s go-to setting, but the festive board (based off an 1805 mural titled Kidai Shôran) is an inviting centerpiece, replete with little people scurrying about.

Even better are the occupation cards, each of which features charming artwork and a unique personality. This lends itself to jokey storytelling, and soon, players are proudly boasting about their candy makers and sumo wrestlers, offering up colorful backstories or ongoing commentary about their lives. When my friend Sly proved to be incapable of feeding her vendors on a regular basis, we spun tales of how she was a terrible boss, forcing her workers to churn out goods in return for nary a grain of rice. I believe the term “North Korea” was used. This was fun.

And then there’s the inevitable moment when you and your opponent both install vendors in the same shop (each shop can accommodate two), and wouldn’t you know it: your guys offer the exact same service. Suddenly, the two of you are wooing a third player, encouraging them to swing by and use YOUR charcoal peddler, not your rival’s pine wreath supplier. You’ll be a sandwich board and a sample tray away from a full-fledged marketing blitz.

The salt peddler and dice maker work in the same shop, but players can only make deals with one of them. If I were the blue player, I might want to pay a coin and grab some lumber from the dice maker, but doing so would cause him to level up. Furthermore, he’s already leveled up twice (as indicated by the meeple); so this would send him into retirement. It’s probably wiser to take the rice from the peddler. But then that totally EFFS my strategy. Ikiiiiiiii!!!! [shaking my fist]

It’s worth noting that Iki has a surprisingly large amount of variability. At first blush, this may not appear to be the case: there are always the same six buildings to construct, there are always the same four starter cards to choose from, and many of the occupation cards will resurface time and time again. However, the order in which those occupations emerge from the deck keeps everything — everything — variable. And where those occupations wind up in the market also plays a remarkably large role in keeping each session of Iki fresh and unique. Oh, and then there are those pesky fires. One bad blaze, and the entire balance of the game can be thrown into question.

There’s only one significant drawback to Iki: it’s not widely available. I tracked down my copy by going to the marketplace at boardgamegeek.com. It was a hassle, but so so worth it. I’m not sure if Iki will find a wide audience, but hopefully awareness will translate into demand, and with any luck, one of the big game publishers will scoop up the rights and give this game the distribution it deserves.

Should you encounter this game somewhere, do not hesitate for one nanosecond. Grab it, invite your friends over, and prepare for a thinky, occasionally rowdy, and totally FUN experience. Iki is perfection (except for its questionably translated rulebook).

PURE JOY.

Have you played Iki? What do you think?