As I’ve tumbled down the slippery slope of the gaming hobby, I’ve encountered, resisted, and ultimately succumbed to a phenomenon called “The Cult of the New.” It’s a terrible, terrible affliction that has gamers flocking like zombies to the new and exciting titles rolling off the assembly lines. However, this comes at the expense of older, equally impressive options, which can be overlooked in the mad scramble for fresh, new playthings.

Thankfully, to help separate the wheat from the chaff, there are tons of gaming podcasts out there, and one of them, The Secret Cabal Gaming Podcast, recently profiled a groovy game from the mid-Aughts called Railways of the World by Martin Wallace. Their enthusiasm was unbridled, to put it mildly. Here was a game that promised excellent strategy, interaction, components, and variety — one of their favorites of all time.

Could it be that good? I had to try it for myself.

Originally titled Railroad Tycoon (a tie-in with the popular video game series), Railways of the World comes in a giant, heavy box full of trains, tracks, buildings, and maps. Just opening this beast feels epic, and the beautifully illustrated maps and chunky components immediately conjure up childhood feelings of PLAY — so many colors, so many little structures. I was never a model train kid, but I did love creating worlds with Legos, building blocks, Matchbox cars, and whatever else was around (perhaps a dinosaur or Fisher Price lady). This game conjures up those warm memories — although, the lack of dinosaurs is an issue.

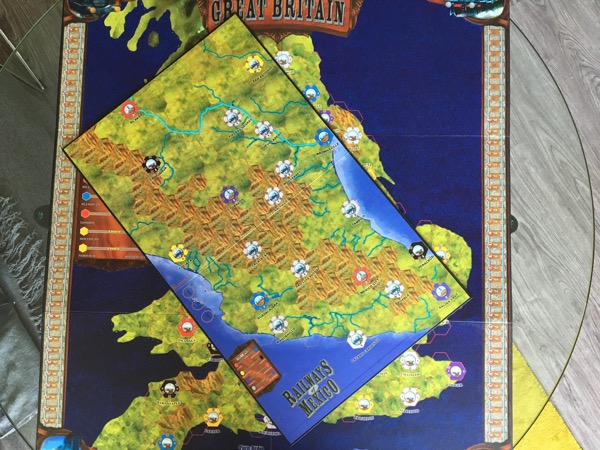

But enough earnest nostalgia: we’re not here to examine my boyhood (at least, I don’t think we are). Let’s talk about this game, which features two maps: a smaller depiction of Mexico, suitable for two or three players, and then a gargantuan Eastern U.S. map that’s so big it literally doesn’t even fit on my table. That’s right: to play this game, I have to outsource my fun to my friends’ dining room tables (luckily they’re all very accommodating).

My table runneth over.

This is the Eastern U.S. board, along with a standard DirecTV remote for scale. ‘uuuge.

With the scoreboard, space becomes even more limited.

Not even halfway through setup, and we are officially out of room.

The expansion Railways of Great Britain is equally as large, but at least the scoring track is integrated into the map. Feet not included.

Luckily, the Mexico map is small and table-friendly.

The big map allows for up to six players to play, and that’s pretty much what we did recently when five of us gathered at our friend Sly’s place for an epic, excellent evening of Railways. The conceit is simple: players start with no money whatsoever. Over the course of the game, they will take out bonds, build their railway network, deliver goods, increase profits, and improve their locomotives — all in the pursuit of pure dominance. It’s great.

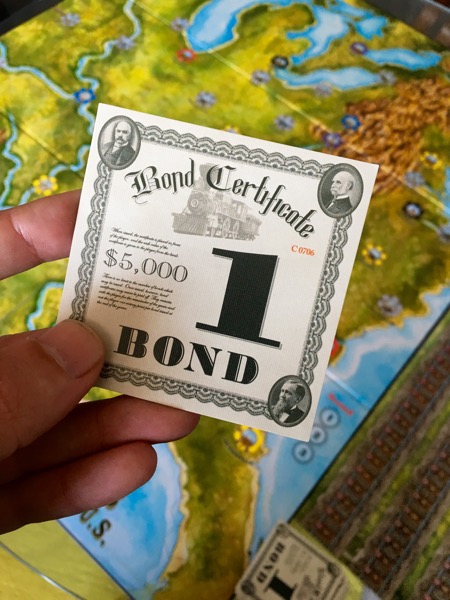

Every round begins with an auction for turn order. I bid $1,000, you bid $2,000, someone else jumps up to $4,000, and then we go ‘round and ‘round until all but one person has passed. Pretty simple stuff, but somehow entertaining every time (and I don’t even like auctions). Of course, at the start of the game, everyone is penniless, which means that whoever wins the auction must take out bonds to fund their bid. Bonds are necessary evils in Railways. Everyone must take one at some point, and in return they receive $5,000 cash. Unfortunately, at the end of the round, players must then pay $1,000 to the bank for every bond they have, and if they don’t have that money, then it’s time for another bond. Yay, debt! Oh, and at the end of the game, everyone loses one point per bond they have. Boo, debt!

Bond. Rail bond.

Bonds never go away. Ever. So, take them with caution. But don’t be too afraid of them. Sometimes that cash infusion is exactly what you need to get an edge on the competition.

Players may use that cash to build train lines between cities on the board, with each track tile costing a certain amount depending on the terrain it traverses (cheapest for open land, most expensive for mountains and ridges). And just so there’s no confusion, players then place a train of their color on their recently completed track — a handy way of politely saying “This track is mine, bitches.”

An undeveloped swath of land.

The hexagons dictate where we can build train tracks. Forging across open land is cheapest. Crossing a river will set you back a few extra bucks. Mountains are even pricier. And traversing a ridge (the heavy brown outlines) is the mostest expensivest thing EVAAR.

A tiny rail link in Mexico.

Not only does placing tiny locomotives add some visual pizazz to the board, but it helps identify who will receive points when deliveries zip across the ever growing network of railways.

Deliveries, you say?

Yes, deliveries. You see, every city on the board has a unique color (red, black, yellow, blue, purple, gray), and that color represents a demand. For instance, people in the red cities want red goods; people in blue cities want blue goods. You get the point.

The goods are represented by cubes, which are randomly scattered amongst the cities. In order to earn points, players must deliver cubes to the cities that want them, and what’s the best way to deliver goods in a train game? You guessed it: TRAINS.

Baltimore is a yellow city, and thus would like Philly’s yellow cube, er, goods. DC and Dover haven’t quite established a demand just yet, which is why they’re simply gray. But we’ll get back to that…

It’s pretty straightforward: deliver a purple cube to a purple city, and you’ll earn points for every rail link you use. One link is one point. Two links is two points. Three links is three points. I think you get it. Basically, the more cities your goods travel through, the more points you’ll get. If you’re really in a bind, you can also use another player’s links, but they’ll get those points, not you (so, if I delivered across two of my links and one of yours, I would get two points, you would get one — isn’t sharing lovely?).

In the beginning though, one cannot simply deliver across two or three links. Players must upgrade their engines first. Everyone starts with a Level One locomotive, which allows them to deliver goods across only one link. By spending increasingly large amounts of money, players can upgrade to a Level Two, Three, and up to an Eight engine, which allows delivery across longer swaths of land. A Level Eight locomotive, for instance, allows players to transport a good across eight links, and in an ideal world, that could generate eight points in one turn (which is amazing).

The blue train company has established a link between Baltimore and Philly. Finally, someone can deliver that yellow cube!

The yellow train company has decided to skip Philadelphia altogether and create a link between Baltimore and New York. If yellow had a Level 2 locomotive, it could deliver the blue cube from NY to Baltimore and then to Philadelphia by way of Blue’s track. This is sort of dumb though because yellow would essentially be giving blue a free point. But it’s fun to think about!

Pure madness! Blue has crossed various mountains and ridges, connecting Pittsburgh to Baltimore. With a level 2 engine, blue could then send two blue cubes to Philly via Baltimore, earning two points for each cube. Huzzah! A BOON FOR BLUE CUBE LOVERS IN EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

And with a level 3 engine, blue could even send a black cube from Philly all the way to Columbus, OH (although, this means giving red a freebie point).

And this is just one quarter of the board.

Every point moves players up an income track. After three turns, the round ends, and everyone gets money based on where they are on said income track. In other words, the better your engine, the more points you’ll generally get, and the more points you get, the more money you’ll earn — at least until your train company becomes too unwieldy and actually begins to cost you money, but whatevs.

With the money rolling in, you’ll be able to do things like Urbanize, an expensive action which allows players to change a gray city into a color of their choice (excluding red). It’s a simple move, but it can have huge ramifications. Urbanization can transform a lifeless rail network into a money-making, point-generating monster. It can also totally short circuit someone’s ambitious plans (this happened to me, and I’m still bitter). Most importantly, it can prolong the length of the game.

Urbanizing Norfolk into a city that wants — nay, CRAVES — yellow goods. Now would be a good time to build a railway to Richmond…

Railways of the World ends when a certain number of cities have been emptied of their cubes. By Urbanizing, players are able to introduce new cubes to the board, thus slowing the ticking clock of the game. This can be a serious issue when a person in the lead starts emptying out cities solely to trigger the end before anyone can catch up. Just one of the many strategic nuances of the game.

One of several chunky figures that can demarcate an empty city.

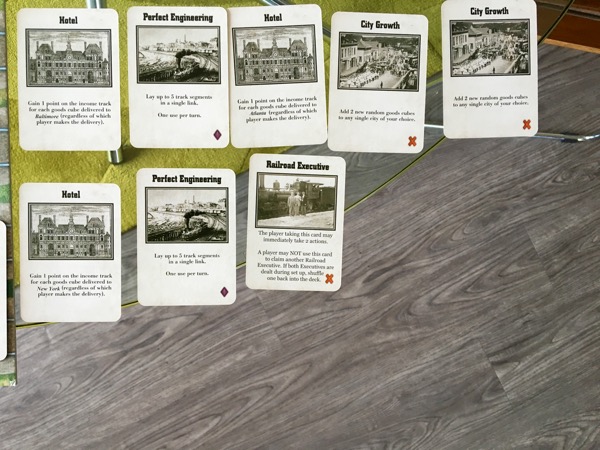

One last thing players may do is grab a Railroad Operations card, which provides a special power. These cards are first come first serve, with a new one emerging every round. More often than not, they’re a major consideration during the player order auction at the top of every round. Railroad Operation cards offer essential advantages, but are they worth sacrificing a full turn and/or bidding money to claim?

A typical smattering of Railroad Operations cards.

This is one of the many wonderful dilemmas that Railways of the World sticks its players into. The mechanics of the game are basic: build links, upgrade trains, deliver goods, etc…. but as a web of railways slowly creeps across the board, these basic mechanics give way to deep, strategic quandaries with layers upon layers of decision-making. Everything becomes a crisis.

Do I blow through all my money to secure the first spot in player order? Or do I save it for a new train upgrade?

Do I take on another bond to build a link through the mountains? Or do I wait another round after I’ve earned more income?

Do I deliver that red cube to New York this turn? Or do I try to add another link to the route for an extra point? And if I do that, what if someone has already delivered the red cube? Where are the other red cube? Should I start building towards Chicago instead?

These are the things that will race through your brain faster than the time machine in Back to the Future III (labored train reference!). I wish I could really express the amount of delicious tension this game generates, but you’ll just have to take my word for it.

And then there’s the interactivity. Railways manages an incredible feat: it has players all up in each other’s grills (or cowcatchers) without actually being a mean game. In other words, it’s cutthroat but not nasty. More often than not, there’s a good deal of sportsmanship around the table as people applaud a particularly impressive delivery or deft rail placement. And that’s nice.

Of course, there are occasional obnoxious moves to be made, and full disclosure, I’ve been known to do them from time to time. It’s usually nothing more than me totally getting in everyone’s way, and I swear I don’t do it to be annoying or spiteful — I have my own strategies, after all — but I have received SEVERAL groans from the would-be tycoons around the table. Sorry?

A perfect example of me (blue) pestering my friend (yellow). Listen, I had a hotel in Manchester. Of COURSE I was going to get in on that sweet, sweet turf.

To be fair, the British map is perfect for in-your-face railroading. Check out this mess at the end of a recent game.

But let’s get back to interactivity. Railways makes sure everyone is invested in the game at all times. Whether players are vying over dwindling goods, disappearing land, or coveted Railroad Operations cards, there’s a lot to keep your eyes on. Plus, I didn’t even mention the bonus points players get if they’re the first to link up two faraway cities to each other: just another facet that keeps everyone on their toes. Oh, and there are even more points to be earned by completing secret end game objectives — things like Most Money, Most Rail Links, Most Connected Cities etc. These aren’t central to the game, but they ensure that all players keep tabs on everyone else at all time.

How long the game lasts depends entirely on the amount of players and the speed with which people empty goods out from cities. Generally though, Railways of the World takes a few hours. I’ve played it with two people (Mexico map), four people (Great Britain map — not included), and five people (Eastern U.S.). The latter game, which included a rules explanation, began at 10 PM and ended close to 2:30 AM. It was long.

The final, epic board state. Note the all-important bottle-opener to the side. Our friend Drew demolished us.

But don’t be scared off. The time FLEW by, and by the end, the entire experience felt big, hearty, and downright epic. The game starts off with an empty board and penniless players, and by the end, we’ve all carved out empires on a massive, colorful map littered with trains, rails, and a heaping handful of structures. The sense of growth and accomplishment is wonderful, but more importantly, the game gives you that deeply satisfying feeling that comes from having spent hours and hours fully engaged with your friends (and perhaps some wine — highly recommended). You and your group will sit back and marvel at the train networks you’ve created, you’ll play back the critical turning points in the game, you’ll do a postgame report on your strategy, you’ll chuckle about vicious train confrontations, and you’ll think about all the things you’ll do differently next time. And then, when that’s all done, and you’ll laugh anew about how much time you’ve spent playing the game and how quickly it zipped by.

The end of a two-player game with my friend Sly. This was our first go at it, and we made the ridiculous mistake of starting off in the mountains. Disaster.

Utter chaos at the end of Railways of Great Britain, which Sly ultimately won.

Railways is a joy. I would play it every week if I could. It’s the sort of game that is simple to teach but feels infinitely deep with its strategy. The gameplay is truly awesome, and the social experience wildly fulfilling. Pulling out the game feels like embarking on an adventure. I become downright giddy knowing I’m about to spend the next few hours with my friends enjoying their company, cracking jokes, perhaps drinking aforementioned wine, and playing a fantastic game in the process.

Railways of the World isn’t merely a game you play on game night: it’s an event. It’s a Saturday evening plan. It’s a lazy Sunday centerpiece. To me, it brings out the best in gaming and reminds me all over again why I fell in love with this hobby in the first place. I can’t recommend this game highly enough (although, beware: it’s pricey at $75). Find yourself a big table, invite some friends over, stock the fridge with the libation of your choice, and dive into Railways of the World.